Covariance shrinkage for begginers with Python implementation

Published:

Covariance matrices are one of the most important objects in statistics and machine learning, essential to many algorithms. But estimating covariance matrices can be difficult, especially in high-dimensional settings. In this post we introduce covariance shrinkage, a technique to improve covariance matrix estimation. We also provide a PyTorch implementation of a popular shrinkage technique, the Oracle Approximating Shrinkage (OAS) estimator.

Introduction

One issue with estimating the true covariance matrix \(\Sigma\) for a given population or random variable is that, if \(p\) is the number of dimensions, \(\Sigma\) has \(p \times p\) entries, of which \((p+1)p/2\) are independent parameters that need to be estimated (this number comes from considering the symmetry of covariance matrices1). This means that the number of parameters needed to estimate the covariance matrix grows fast with the number of dimensions. That is, covariance estimation suffers from the curse of dimensionality.

An interesting and challenging statistical problem is how to estimate a covariance matrix when the number of observations \(n\) is not large compared to the number of dimensions \(p\).

The simplest way to estimate the covariance matrix is to use the sample covariance \(S\). Given a dataset of \(n\) observations of \(p\)-dimensional random variable \(X \in \mathbb{R}^p\), with the observations labeled as \(X_1, X_2, \ldots, X_n\), the sample covariance matrix is defined as

\[S = \frac{1}{n-1} \sum_{i=1}^n (X_i - \bar{X})(X_i - \bar{X})^T\]where \(\bar{X}\) is the sample mean. \(S\) is an unbiased estimator of the true population covariance matrix, which means that the expected value of \(S\) is the true covariance matrix.

However, the sample covariance has some drawbacks as an estimator. Mainly, \(S\) is unstable when \(n\) is small compared to \(p\), meaning that it can have large errors with respect to the true covariance \(\Sigma\).

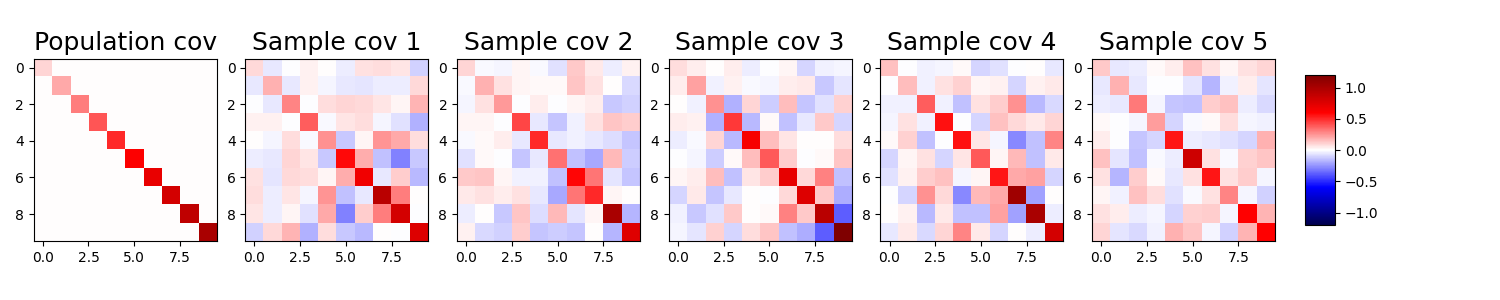

Let’s visualize this variability with some simulations. We first define a diagonal covariance matrix \(\Sigma\). Then we take 20 samples from a 10-dimensional Gaussian distribution that has \(\Sigma\) as its true covariance matrix. Then we compute the sample covariance matrix \(S\) for these observations. We repeat this process 5 times and plot the resulting sample covariance matrices.

import torch

from torch.distributions import MultivariateNormal

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

torch.manual_seed(2)

# Simulation parameters

n_dim = 10 # Number of dimensions of the random variable

n_samples = 20 # Number of samples to use

n_reps = 5 # Number of sample covariance matrices to compute

# True covariance matrix

cov_pop = torch.linspace(start=0.1, end=1, steps=n_dim)

cov_pop = torch.diag(cov_pop)

# Compute sample covariance matrices

covs_sample = []

for _ in range(n_reps):

X = MultivariateNormal(torch.zeros(n_dim), cov_pop).sample((n_samples,))

covs_sample.append(torch.cov(X.T))

# Plot sample covariance matrices

max_val = 1.2

fig, axs = plt.subplots(1, n_reps+1, figsize=(15, 3))

# Plot and store the image objects

im = axs[0].imshow(cov_pop, cmap='seismic', vmin=-max_val, vmax=max_val)

axs[0].set_title("Population cov", fontsize=18)

for i, ax in enumerate(axs[1:]):

ax.imshow(covs_sample[i], cmap='seismic', vmin=-max_val, vmax=max_val)

ax.set_title(f"Sample cov {i+1}", fontsize=18)

plt.tight_layout()

# Adjust the subplots to make room for the color bar

fig.subplots_adjust(right=0.85)

# Add an axes for the color bar on the right

cbar_ax = fig.add_axes([0.87, 0.25, 0.02, 0.5])

# Add the color bar to the figure

fig.colorbar(im, cax=cbar_ax)

plt.show()

We see that for each different draw of 20 samples the corresponding \(S\) changes considerably, because of the high variability in the sample covariance matrix.

Another problem with \(S\) as an estimator, is that many applications require inverting the covariance matrix. When \(p > n\), the sample covariance is not even invertible, making \(S\) unsuitable for some applications. But even if \(p<n\) and \(S\) is invertible, the high estimation error in \(S\) can be highly amplified when inverting the matrix.

Thus, the sample covariance matrix might not be the best estimator for some applications. How can we obtain better estimates of the covariance matrix, though? One alternative is to use shrinkage.

Shrinkage estimators

Shrinkage is an essential idea in statistics. Intuitively, if we observe an extreme value in a random sample, it is likely that noise contributed to the extremeness of the value. In other words, we can expect that extreme observed values are not representative of the true underlying parameter. Shrinkage is a statistical procedure to account for this phenomenon when estimating the underlying parameters, by pulling the more extreme values in an observed sample towards the middle. The more extreme the value, the more we shrink it towards the middle. This procedure reduces the variance of the estimates, at the cost of introducing some bias, a classical example of the bias-variance trade-off in statistics.

Shrinkage estimators of the covariance incorporate this idea into covariance estimation. Like in the example above, the idea consists of shrinking the observed sample covariance towards a “middle” or “target” value. This will reduce the variance of the estimates, at the cost of introducing some bias.

What is a good target matrix to shrink the sample covariance towards? A popular target is the following diagonal matrix, which is an isotropic estimator of the covariance matrix:

\[\hat{F} = \frac{1}{p} \text{tr}(S) I\]where \(I\) is the identity matrix. We can think of \(\hat{F}\) as an estimator of \(\Sigma\) that has low variance but possibly high bias.

The next question to ask ourselves is, how do we “shrink” the sample covariance towards the target matrix \(\hat{F}\)? Linear shrinkage estimators do this by taking a linear combination of the sample covariance matrix \(S\) and the target matrix \(\hat{F}\), with a parameter \(\rho\) that controls the amount of shrinkage:

\[\hat{\Sigma} = (1-\rho) S + \rho \hat{F}\]When \(\rho = 0\), the estimate is the sample covariance matrix.

The last question we need to ask ourselves is how to find a value of \(\rho\) that results in a good estimate. This is a challenging problem, as the optimal value of \(\rho\) depends on the true covariance matrix, which is unknown. We turn to this question in the next section.

Oracle Approximating Shrinkage estimator (with implementation)

A typical way to find a good value of \(\rho\) is to start by assuming that the true covariance matrix \(\Sigma\) is known, and choosing an estimation criterion to minimize. For example, one common criterion to optimize is the mean squared error (MSE) between the estimated covariance matrix \(\hat{\Sigma}\) and the true covariance matrix \(\Sigma\):

\[\min_{\rho} \mathbb{E} \left[ \left\| \hat{\Sigma} - \Sigma \right\|_F^2 \right]\]where \(\| \cdot \|_F\) is the Frobenius norm2. Under a known \(\Sigma\), it is often possible to find a formula for what the optimal value of \(\rho\) is, which can be denoted as the oracle value of \(\rho\).

In practice, however, we do not know the true covariance matrix \(\Sigma\). Thus, the challenge is to find a way to approximate the unknown optimal value of \(\rho\) when \(\Sigma\) is unknown.

This is what Oracle Approximating Shrinkage (OAS) does: it proposes a formula to approximate the oracle value of \(\rho\) that minimizes the MSE, under the assumption that the data is Gaussian distributed. This method performs particularly well when the number of observations \(n\) is small compared to the number of dimensions \(p\). The OAS formula for \(\rho\) is as follows:

\[\hat{\rho}_{OAS} = \frac{(1-2p)\mathrm{Tr}(S^2) + \mathrm{Tr}^2(S)} {(n+1-2/p) (\mathrm{Tr}(S^2) - \mathrm{Tr}^2(S)/p}\]where we cap the result at 1 (if the value of the formula above is larger than one, we set \(\hat{\rho}_{OAS}=1\)).

Let’s implement the OAS estimator in PyTorch:

def isotropic_estimator(sample_covariance):

"""Isotropic covariance estimate with same trace as sample.

Arguments:

----------

sample_covariance : torch.Tensor

Sample covariance matrix.

"""

n_dim = sample_covariance.shape[0]

return torch.eye(n_dim) * torch.trace(sample_covariance) / n_dim

def oas_shrinkage(sample_covariance, n_samples):

"""Get OAS shrinkage parameter.

Arguments:

----------

sample_covariance : torch.Tensor

Sample covariance matrix.

"""

n_dim = sample_covariance.shape[0]

tr_cov = torch.trace(sample_covariance)

tr_prod = torch.sum(sample_covariance ** 2)

shrinkage = (

(1 - 2 / n_dim) * tr_prod + tr_cov ** 2

) / (

(n_samples + 1 - 2 / n_dim) * (tr_prod - tr_cov ** 2 / n_dim)

)

shrinkage = min(1, shrinkage)

return shrinkage

def oas_estimator(X, assume_centered=False):

"""Oracle Approximating Shrinkage (OAS) covariance estimate.

Arguments:

----------

X : torch.Tensor

Data matrix with shape (n_samples, n_features).

"""

n_samples = X.shape[0]

# Compute sample covariance

if not assume_centered:

sample_covariance = torch.cov(X.T)

else:

sample_covariance = X.T @ X / n_samples

# Compute isotropic estimator F

isotropic = isotropic_estimator(sample_covariance)

# Compute OAS shrinkage parameter

shrinkage = oas_shrinkage(sample_covariance, n_samples)

# Compute OAS shrinkage covariance estimate

oas_estimate = (1 - shrinkage) * sample_covariance + shrinkage * isotropic

return oas_estimate

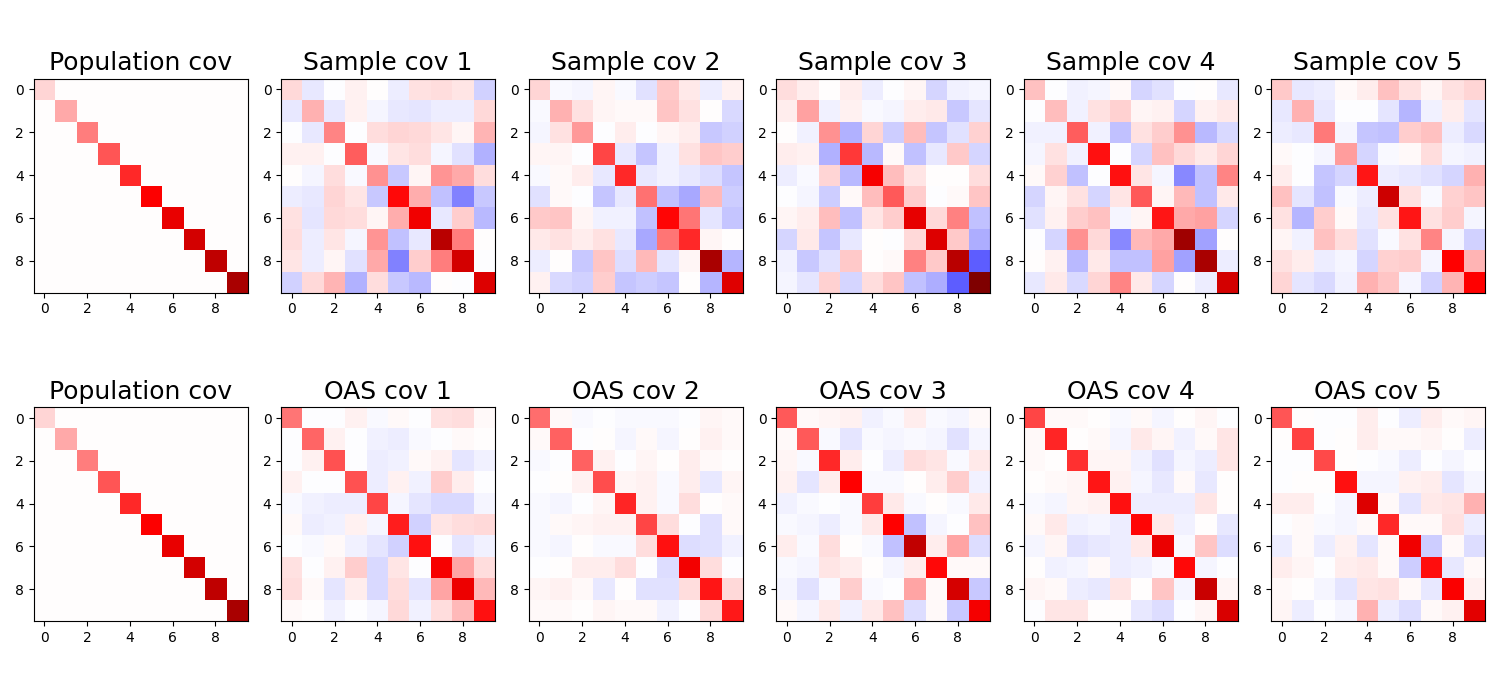

Let’s now test the OAS estimator with the same simulations as before. We again sample 20 observations from a 10-dimensional Gaussian, and we compute both the sample covariance matrix \(S\) and the OAS estimator \(\hat{\Sigma}\) for the data. We repeat this process 5 times, and plot both the covariance estimates, and compute the MSE between the true covariance matrix and both estimators.

n_dim = 10

n_samples = 20

n_reps = 5

# Compute sample covariance matrices

covs_sample = []

covs_oas = []

for _ in range(n_reps):

X = MultivariateNormal(torch.zeros(n_dim), cov_pop).sample((n_samples,))

covs_sample.append(torch.cov(X.T))

covs_oas.append(oas_estimator(X))

# Plot sample covariance matrices

max_val = 1.2

fig, axs = plt.subplots(2, n_reps+1, figsize=(15, 7))

axs[0,0].imshow(cov_pop, cmap='seismic', vmin=-max_val, vmax=max_val)

axs[0,0].set_title("Population cov", fontsize=18)

axs[1,0].imshow(cov_pop, cmap='seismic', vmin=-max_val, vmax=max_val)

axs[1,0].set_title("Population cov", fontsize=18)

for i in range(n_reps):

axs[0,1+i].imshow(covs_sample[i], cmap='seismic', vmin=-max_val, vmax=max_val)

axs[0,1+i].set_title(f"Sample cov {i+1}", fontsize=18)

axs[1,1+i].imshow(covs_oas[i], cmap='seismic', vmin=-max_val, vmax=max_val)

axs[1,1+i].set_title(f"OAS cov {i+1}", fontsize=18)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# Compute mean squared error

mse_sample = torch.stack([torch.linalg.norm(cov_pop - cov) ** 2 for cov in covs_sample]).mean()

mse_oas = torch.stack([torch.linalg.norm(cov_pop - cov) ** 2 for cov in covs_oas]).mean()

print(f"MSE sample covariance: {mse_sample}")

print(f"MSE OAS covariance: {mse_oas}")

MSE sample covariance: 1.9461839199066162

MSE OAS covariance: 0.659830629825592

We see that:

- OAS estimator provides a more stable estimate than \(S\)

- OAS estimator diagonal elements are more biased than \(S\)

- OAS estimator has lower MSE than \(S\)

Linear Discriminant Analysis with shrinkage

Let’s next compare the OAS estimator to the sample covariance estimator in a practical setting. For this, we will use Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) as applied to the MNIST dataset.

Linear Discriminant Analysis

LDA is a standard technique for dimensionality reduction and classification. In a labeled dataset, LDA learns the filters that maximize the separation between classes, while minimizing the within-class variability. This goal can be mathematically formulated as follows:

- In a dataset with \(C\) classes, the between-class scatter matrix \(S_B = \frac{1}{C}\sum_{i=1}^C (\mu_i - \mu)(\mu_i - \mu)^T\) (i.e. covariance of the class means centered around the global mean) indicates how the class means are spread out in the data space. In this formula, \(\mu_i\) is the mean of class \(i\), and \(\mu\) is the global mean.

- The within-class scatter matrix \(S_W = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^C \sum_{x \in X_i} (x - \mu_i)(x - \mu_i)^T\), where \(N\) is the total number of samples, and \(X_i\) is the residual covariance around the class means, i.e. the within-class variability.

- If we project the data along vector \(w\), the variance between classes will be given by \(w^T S_B w\), and the variance within classes will be given by \(w^T S_W w\)

- Thus, the filters \(w\) that maximize between-class separation while minimizing within-class variance are the directions that maximize the following ratio:

It turns out that the directions \(w\) that maximize the ratio above are the eigenvectors of the matrix \(S_W^{-1} S_B\) (see here). Thus, we can find the LDA filters by computing the two scatter matrices, inverting \(S_W\), and computing the eigenvectors of the product \(S_W^{-1} S_B\). LDA is also a linear classifier, which uses these projection to classify new data points based on how close they are to the class means.

The quality of the LDA filters depends on the quality of the estimates of \(S_W\) and \(S_B\). That’s why LDA is a good application to compare covariance estimators: the quality of the LDA filters (which we can measure by the classification accuracy) can be used as a proxy for the quality of the covariance estimates.

Applying LDA to MNIST

Let’s first load the MNIST dataset using the torchvision package.

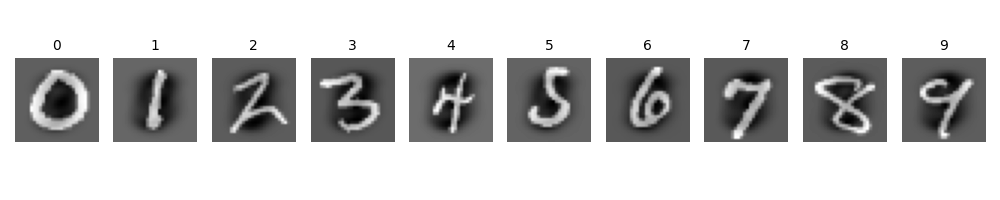

Note that we modify the dataset in two ways to better suit our example. First, we subsample the number of images, keeping only 2000 images so that the number of observations \(n\) is close to the number of dimensions \(p\). Second, we remove from the learning procedure some pixels that have zero variance (i.e. they are constant across all images) to avoid singular covariance matrices.

import torchvision

# Download and load training and test datasets

trainset = torchvision.datasets.MNIST(root='./data', train=True, download=True)

testset = torchvision.datasets.MNIST(root='./data', train=False, download=True)

# Reshape images into vectors

n_samples, n_row, n_col = trainset.data.shape

n_dim = trainset.data[0].numel()

x_train = trainset.data.reshape(-1, n_dim).float()

y_train = trainset.targets

x_test = testset.data.reshape(-1, n_dim).float()

y_test = testset.targets

# Subsample data

N_SUBSAMPLE = 2000 # Number of images to keep

rand_idx = torch.randperm(x_train.shape[0])

rand_idx = torch.sort(rand_idx[:N_SUBSAMPLE]).values

x_train = x_train[rand_idx]

y_train = y_train[rand_idx]

x_train = x_train[:N_SUBSAMPLE]

y_train = y_train[:N_SUBSAMPLE]

# Mask pixels with zero variance

mask = x_train.std(dim=0) > 0

x_train = x_train[:, mask]

x_test = x_test[:, mask]

def unmask_image(image):

"""Function to return data vector to original shape."""

unmasked = torch.zeros(n_dim)

unmasked[mask] = image

return unmasked

# Scale data and subtract global mean

def scale_and_center(x_train, x_test):

std = x_train.std()

x_train = x_train / std

x_test = x_test / std

global_mean = x_train.mean(axis=0, keepdims=True)

x_train = x_train - global_mean

x_test = x_test - global_mean

return x_train, x_test

# Scale data and subtract global mean

x_train, x_test = scale_and_center(x_train, x_test)

# Plot some images

names = y_train.unique().tolist()

n_classes = len(y_train.unique())

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, n_classes, figsize=(10, 2))

for i in range(n_classes):

ax[i].imshow(

unmask_image(x_train[y_train == i][0]).reshape(n_row, n_col), cmap='gray')

ax[i].axis('off')

ax[i].set_title(names[i], fontsize=10)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Next, let’s compute the scatter matrices \(S_W\) and \(S_B\). Matrix \(S_W\) is estimated both using the sample covariance and the OAS estimator.

# Compute the class means

class_means = torch.stack([x_train[y_train == i].mean(dim=0) for i in range(n_classes)])

mu = class_means.mean(dim=0, keepdim=True)

# Compute between-class scatter matrix

between_class = (class_means - mu).T @ (class_means - mu) / n_classes

# Compute the within-class scatter matrix

x_train_centered = x_train - class_means[y_train]

within_class_sample = x_train_centered.T @ x_train_centered / N_SUBSAMPLE

within_class_oas = oas_estimator(x_train_centered, assume_centered=True)

Then, we compute the LDA filters obtained from each covariance matrix. We add a small value to the diagonal of \(S_W\) for numerical stability:

# Get LDA filters

n_filters = n_classes - 1

def get_lda_filters(between_class, within_class):

within_class_inv = torch.linalg.inv(within_class)

lda_mat = within_class_inv @ between_class

eigvals, eigvecs = torch.linalg.eigh(lda_mat)

filters = eigvecs[:, -n_filters:]

return filters.T

# Get the LDA projections

small_reg = torch.eye(within_class_sample.shape[0]) * 1e-7

lda_filters_sample = get_lda_filters(between_class, within_class_sample + small_reg)

lda_filters_oas = get_lda_filters(between_class, within_class_oas + small_reg)

Let’s now plot the LDA filters obtained with both covariance estimators:

# Plot both LDA filters

fig, axs = plt.subplots(2, 9, figsize=(12, 4))

for i in range(9):

sample_filter_im = unmask_image(lda_filters_sample[i]).reshape(n_row, n_col)

oas_filter_im = unmask_image(lda_filters_oas[i]).reshape(n_row, n_col)

axs[0, i].imshow(sample_filter_im, cmap='gray')

axs[0, i].axis('off')

axs[1, i].imshow(oas_filter_im, cmap='gray')

axs[1, i].axis('off')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

We see that the filters obtained with the sample covariance estimator seem unstable, in that they put most of their weight into a few pixels. The OAS filters are noisy, as we could expect from the small number of samples used, but they are smoother and better distributed across the image.

Finally, we can compute the classification accuracy of the LDA filters

from sklearn.discriminant_analysis import LinearDiscriminantAnalysis

from sklearn.metrics import accuracy_score

def get_filters_accuracy(filters, x_train, y_train, x_test, y_test):

x_train_lda = x_train @ filters.T

x_test_lda = x_test @ filters.T

lda_classifier = LinearDiscriminantAnalysis()

lda_classifier.fit(x_train_lda, y_train)

acc = lda_classifier.score(x_test_lda, y_test)

return acc

# Compute accuracy of LDA filters

sample_acc = get_filters_accuracy(lda_filters_sample, x_train, y_train, x_test, y_test)

oas_acc = get_filters_accuracy(lda_filters_oas, x_train, y_train, x_test, y_test)

print(f"Sample LDA accuracy: {sample_acc:.2f}")

print(f"OAS LDA accuracy: {oas_acc:.2f}")

Sample LDA accuracy: 0.79

OAS LDA accuracy: 0.83

We see that the OAS estimator of \(S_W\) provides a better classification accuracy than the sample covariance estimator. This is a common result in practice, as the OAS estimator provides a more stable estimate of the covariance matrix. In fact, there is an sklearn tutorial comparing the performance of LDA on simulated data with different shrinkage estimators. This problem has also been studied in the literature, for example in the influential paper Regularized Discriminant Analysis.

Conclusion

In this post, we learned that although the sample covariance matrix is a simple and unbiased estimator of the true covariance matrix, it may not be the best estimator for some applications. In particular, when the number of observations is small compared to the number of dimensions, shrinkage estimators can provide more stable and accurate estimates of the covariance matrix. We introduced a type of linear shrinkage estimator, the Oracle Approximating Shrinkage (OAS), which aims to minimize the MSE between the estimated and true covariance matrix. Other shrinkage estimators exist, both of the non-linear type, and also aiming to minimize other criteria, such as in the spectral domain.

The covariance matrix is symmetric, so the number of unique entries is given by those at and below the diagonal. The first row has \(1\) element at/below the diagonal, the second row has \(2\), and so on up to the \(n\)th row, which has \(p\) elements. So the number of unique elements equals the sum \(1 + 2 + \ldots + p\). Note that adding the first and last element equals \(p+1\), adding the second and second-to-last element also equals \(p+1\), and so on. So, we have \(p/2\) pairs of elements that sum to \(p+1\), resulting in the known formula \(1 + 2 + \ldots + p = \frac{(p+1)p}{2}\) ↩

The Frobenius norm of a matrix \(A\) is defined as \(\| A \|_F = \sqrt{\sum_{i,j} A_{ij}^2}\), which also equal to \(\text{tr}(A^T A)\), where \(\text{tr}\) is the trace operator. ↩